Nantucket Shoals Wind Farm Field Monitoring Program: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 4 Current and Potential Future Activities

Chapter 4

Current and Potential Future Activities

Given the scale and complexity of field monitoring efforts to understand potential ecological impacts of offshore wind development in Nantucket Shoals, the importance of collaboration was a common theme throughout the workshop. Several participants pointed to opportunities for collaboration both in driving future monitoring efforts and in making the best use of existing and planned monitoring activities. On the workshop’s first day, several invited speakers shared information about ongoing and planned observations supported by a range of academic, nonprofit, government, and industry groups. Throughout the subsequent conversations, speakers and other attendees considered how these and other programs could be leveraged, combined, and added to in order to generate additional insights and fill knowledge gaps. On the event’s final day, participants discussed future opportunities for collaboration to support a robust, effective, and efficient field monitoring program.

EXISTING AND PLANNED OBSERVATIONS

To inform later discussions on additional observational needs, speakers were invited from federal agencies, industry, and academia to share information on observations that are already being collected in the Nantucket Shoals region.

NERACOOS

Kritzer and Cameron Thompson, NERACOOS, presented on NERACOOS, part of NOAA’s IOOS, a network of people and technology for gathering observational data from the nation’s oceans, coasts, and Great Lakes and for developing monitoring and predictive plans. NERACOOS serves as a coordinating body for observations in waters off the northeastern United States, efforts that are implemented and stewarded by local research organizations and government agencies.

Kritzer described observational efforts operating in the ocean surrounding Nantucket Shoals at multiple spatial and temporal scales. These include some long-term, sustained observations that are relevant to monitoring the ocean’s physical aspects and plankton populations. However, Kritzer highlighted, the relocation of the Coastal Pioneer Array from New England waters to its new location further south has left a gap in sustained physical oceanographic measurements in the region that has yet to be filled. He noted that there is opportunity for more sustained physical measurements in the region that will be more directly relevant to the monitoring needs in the context of offshore wind development, as most current activities track surface and low-atmosphere measurements that are geared toward informing weather forecasting, navigation, and rescue operations.

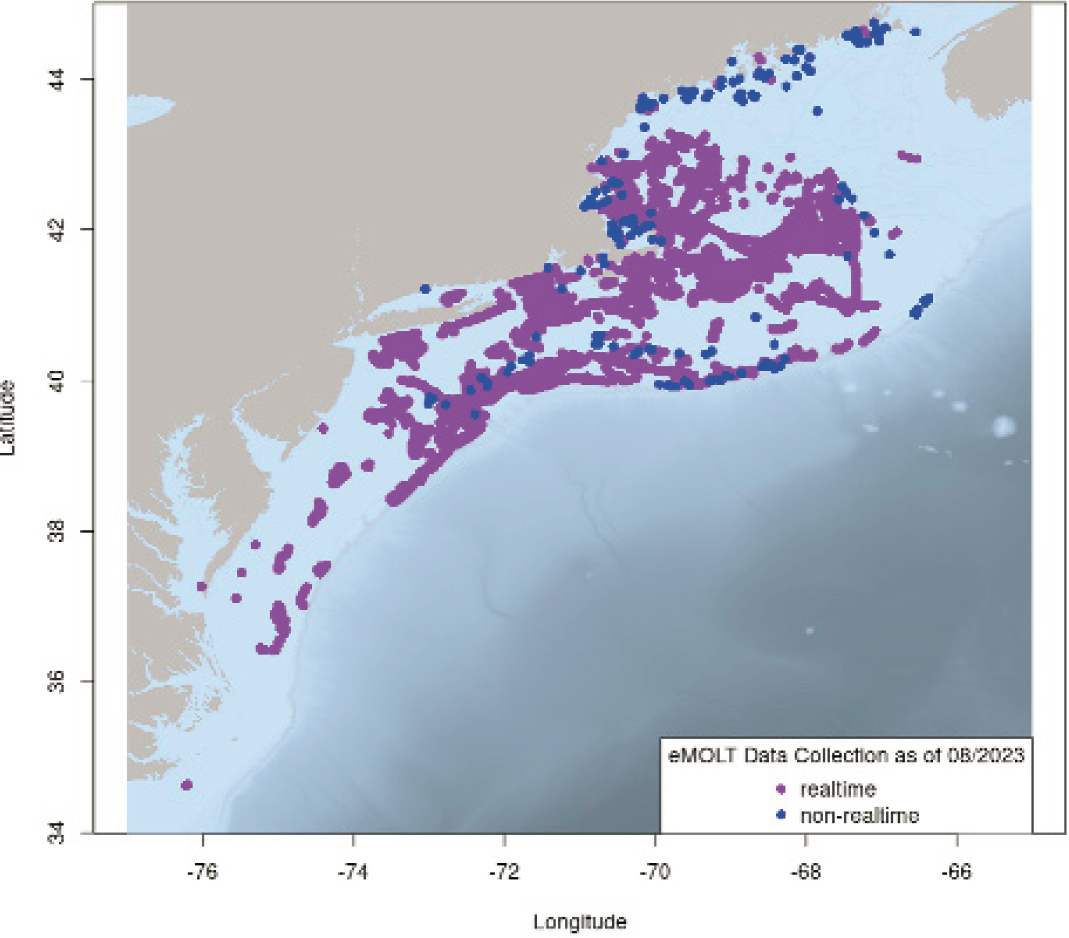

Kritzer outlined several areas where the IOOS network might interact with future wind development and associated monitoring activities in the Nantucket Shoals region. For example, in a program overseen by the Mid-Atlantic Regional Association of Coastal Ocean Observing Systems, high-frequency radar observations are used to collect comprehensive, real-time measurements of surface currents and waves; however, it is expected that this coverage will be disrupted by offshore wind energy infrastructure as it is built out (Figure 3). There is also a network of NERACOOS buoys and other fixed-station observation platforms arrayed across the region (Figure 4).1 Noting that station density is higher where long-standing subsystems are located (in the Gulf of Maine, Narragansett Bay, and Long Island Sound), Kritzer suggested that increasing their number in Nantucket Shoals could help with efforts to track animal behavior. Within the Nantucket Shoals region, the observations are mostly surface observations of sea state and low-atmosphere measurements for weather forecasting. Ocean gliders, used for a variety of purposes, such as mapping cold pools and measuring hurricane conditions, provide short-term observations, although coverage from glider surveys has historically been highest in areas south of Nantucket Shoals. Finally, collaborative observation programs are carried out in partnership with commercial fishermen, known as “ships of opportunity.” These programs, in which fishing vessels are equipped with instruments for measuring bottom temperature, depth, pH, vertical profiles, and other features of the marine environment, represent an additional pool of mobile platforms that could also potentially be recruited to take measurements relevant to Nantucket Shoals field monitoring efforts (Figure 5).

Thompson described zooplankton sampling and monitoring programs in the region that are collecting data on Calanus finmarchicus and other species, primarily aimed at understanding how climate change is affecting their populations. While existing programs provide broad coverage for zooplankton monitoring, he noted that using different methods can limit the ability to compare studies for a comprehensive view. Based on data from particle release studies, the primary productivity for Calanus finmarchicus found in Nantucket Shoals appears to occur in the Gulf of Maine; as plankton drift downstream into the Nantucket Shoals region, it is

___________________

1 https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/acd19f61440f458ca155715baff70236

NOTE: MARACOOS = Mid-Atlantic Regional Association Coastal Ocean Observing System.

SOURCE: Mid-Atlantic Regional Association Coastal Ocean Observing System

NOTES: CDIP = Coastal Data Information Program; MVCO = Martha’s Vineyard Coastal Observatory; NOAA = National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

SOURCE: Northeast Regional Association of Coastal Ocean Observation Systems

SOURCE: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries

understood that populations gradually decline as a result of predation through the fall and winter, although the source and prey aggregating mechanisms for Calanus finmarchicus at Nantucket Shoals are not well understood. Whale studies (e.g., Hudak et al., 2023; Mayo and Marx, 1990) suggest that right whales feed on multiple species, although there is large interannual variability.

Following the remarks from Kritzer and Thompson, several participants suggested potential complementary strategies that could be employed to address some of the monitoring gaps. Mayo suggested incorporating data from drifters, which monitor ocean surface temperatures and currents. Gawarkiewicz highlighted the value of subsurface moorings, which take measurements at the sea surface and fixed depths, for real-time and sustainable observations. Subsurface moorings could be especially critical for measuring salinity, which is known to impact marine life, and these measurements may also help with the important task of understanding the

links between the Gulf of Maine and the Mid-Atlantic Bight. Kritzer and Thompson agreed, noting that shelf break measurements are also important, and Miles added that the Soil and Water Assessment Tool2 could also potentially be a useful resource for data collection.

Tim White, BOEM, noted that observations from buoys, drifters, and satellite imagery have all shown connectivity between the Gulf of Maine and the Mid-Atlantic Bight, including for prey aggregation. In reply to a question from Saba, Chris Orphanides, NOAA, stated that early study data suggest that whales in this area feed on a mix of zooplankton, including Calanus finmarchicus, that are advected there, although he also cited the large interannual variability in conditions and species.

Morse pointed out another challenge, which is that new lease sites in the area will soon be for sale, and it is important to have research-based recommendations for how wind energy structures and long-term monitoring stations should be designed before then. Brian Hooker, BOEM, agreed and emphasized the need for observation strategies that include both zooplankton and oceanographic data that can be used to detect changes in the regional context.

Project WOW

Douglas Nowacek shared the goals and activities of Project WOW (Wildlife and Offshore Wind),3 a transdisciplinary, highly integrated collaboration of experts seeking to comprehensively evaluate how offshore wind energy can affect marine biology. Project WOW aims to create a long-term, adaptive road map for efficient, effective assessments of potential effects throughout the entire WEA development process, from siting through operation.

Critical data for understanding right whale foraging include circulation patterns and changes in the northwest Atlantic Ocean and multiple measurements at multiple timescales to try to understand broad-scale distribution drivers and aggregating mechanisms for plankton. For example, researchers are leveraging observation platforms including satellite imagery, glider data, and high-frequency radar to track currents, sea surface temperature, water mass boundaries, and phytoplankton blooms. Key unresolved questions include the most effective way to sample plankton aggregations and the number of trophic steps there are leading up to the Calanus finmarchicus aggregations that are of concern in the Nantucket Shoals area.

Nowacek also highlighted related ongoing projects that can complement this work with additional ecological insights. One project is the Biodiversity Research Institute’s study, Projecting the Effects of Offshore Wind Mediated Benthic Changes on U.S. Marine Ecosystems, which is developing models of food webs and changes within wind energy development in the northeastern United States.4 Another program, PrePARED (Predators and Prey Around Renewable Energy Developments),

___________________

3 https://offshorewind.env.duke.edu

4 https://briwildlife.org/benthic-changes-on-us-marine-ecosystems

is studying WEA impacts on fish in United Kingdom waters,5 and similar studies are underway in other European regions.

Developer Perspectives

Two speakers provided context on the regulatory, economic, and other drivers of wind energy development and how developers incorporate ecological research and monitoring into their projects. Laura Morse offered her perspective as a former offshore wind developer, and Elizabeth Marsjanik shared Vineyard Offshore’s activities relevant to understanding potential ecological impacts of their ongoing and planned wind energy initiatives.

Morse highlighted the many challenges developers face in building offshore wind infrastructure. Obtaining the necessary funding, permits, insurance, and other supports to begin construction is a long and complex process and marks only the beginning—the construction, operation, and maintenance of offshore wind turbines is also highly complex and costly. It typically takes about 8–10 years for a project to become operational. At the end of this process, Morse noted that offshore wind generation is only considered successful for the industry and consumers if these wind farms lower costs, are profitable, and increase renewable energy use.

Offshore wind developers are required to conduct extensive field surveys and monitoring programs—outlined in the construction operation plan—in the preconstruction phase. They then conduct short-term monitoring and mitigation during construction, as well as long-term monitoring after construction. This monitoring covers multiple variables related to potential impacts on marine mammals, fish, and natural and anthropogenic hazards. Morse said that a lack of cohesive requirements, multiple disconnected research programs, and deployment conflicts or inefficiencies can make these monitoring efforts challenging to implement. They are also expensive and require large amounts of equipment, require intense collaboration and involve multiple data pathways, and can sometimes lead to conflicts or duplicated efforts.

One particularly vexing aspect is that different states have different requirements, and these are also different from federal requirements, Morse said. The onus is on the developer to interpret complex requirements and navigate approval processes with multiple jurisdictions throughout the years-long planning stages across a multitude of projects. As construction gets closer, the processes become clearer, but Morse suggested that there could be opportunities for regulators to encourage efficiencies and optimizations, such as the integration of data from existing hydrodynamics monitoring programs or benthic long-term surveys at earlier stages.

She also highlighted a need for more cohesive monitoring requirements across state and federal contexts. Acknowledging the large amount of data to be collected, she underscored the importance of ensuring that these requirements are achievable

___________________

and practical for developers, scientists, and regulators to execute. She suggested that efficiencies could be gained if the offshore wind community can take a multidisciplinary approach; tap into appropriate funding pools; and leverage expertise, lessons learned, and project management support from relevant partners. For example, she pointed to existing organizations with relevant expertise, including IOOS, the Regional Wildlife Science Collaborative for Offshore Wind (RWSC), and the Responsible Offshore Science Alliance as potential players to lead coordination and project management. She suggested that these efforts could also benefit from greater alignment with NOAA’s science and technology focus areas6 and by learning from other relevant projects, such as the Coastal Pioneer Array and experiences with oil and gas development in the Arctic.

Marsjanik said that Vineyard Offshore is passionate about being a part of the climate solution and takes monitoring requirements seriously in its efforts to promote responsible wind energy development. The company currently has three projects and lease areas in the New England region, with several turbines already generating renewable energy.

Morse highlighted in her remarks that Vineyard Offshore is responsible for conducting multiple monitoring studies at different stages during wind development planning, construction, and deployment. As part of these efforts, the company employs weather and site assessment plan buoys, which provide wind predictions to inform ideal construction windows and estimated energy generation, as well as acoustic monitors. Data are also shared with multiple projects, such as Project Ocean W’aKEs. They also partner with commercial fishing vessels to conduct ecological studies and with technology firms to perform data analysis.

To facilitate greater coordination and efficiency in these and future monitoring efforts, Marsjanik said that it would help greatly if state and federal regulators had better alignment in terms of the number and types of studies required. She also noted that budgets for research and monitoring are often more constrained in the earlier planning phases and that more funding can often be provided once the project is operating under capital expenses. In addition, she said that resource coordination, data-sharing, and frequent publication of findings would be helpful to avoid duplicating efforts and to enrich the knowledge base. She suggested that future studies could help to establish a baseline for the area, enable situational awareness for other species in WEAs, and provide more insights into potential onshore flora and fauna dynamics that might be relevant to what is happening in offshore wind areas.

___________________

6 https://sciencecouncil.noaa.gov/noaa-science-technology-focus-areas

Discussion

Responding to and building upon the presentations, workshop participants discussed issues around data best practices, study motivations, and the physics–biology connections within the ocean system.

Thompson asked about best practices for data management, and Morse replied that some organizations have data governance and management recommendations, and some regulations stipulate data-sharing (within proprietary limits). When followed, best practices, especially those that facilitate leveraging existing resources and expertise, can improve the utility of data and the quality of analyses. Morse and Leung also commented that there are high financial and environmental costs to collecting and working with the large volumes of data required for these monitoring efforts, making it important to carefully consider what types of data are going to be most useful. Leung suggested that research organizations could focus on “future-proofing” their work by recognizing these high costs and allowing for technology changes when planning studies. In addition, he pointed out that investment interest in “blue economy” data is rising and noted that it would be helpful if commercially collected data, which is often inaccessible, could be made more widely available.

Furukawa asked whether monitoring was performed to fulfill regulatory requirements or to address stakeholder concerns. Morse replied that both drivers play a role. While regulatory requirements must be the priority for companies, she said, they also pay careful attention to stakeholder concerns, especially those that are voiced loudly. She noted that companies are unlikely to fund additional monitoring without regulatory requirements demanding certain data. For example, ocean acidification could be an important issue, but collecting data relevant to this has not gained regulatory traction. She noted that regulators are also highly motivated by litigation avoidance and are therefore themselves focused on understanding and anticipating the concerns of various stakeholders. Marsjanik and Morse also agreed that regulators do listen to concerns of stakeholders, underscoring the importance of engaging multiple stakeholder groups in discussions around the potential impacts of offshore wind and relevant monitoring needs.

Furukawa pointed out that regulations are generally written to protect ocean biology, not physics, and she suggested a greater focus on demonstrating the interconnections between the two. Saba wondered if fishery monitoring efforts could help to accomplish that goal, and Marsjanik replied that monitoring impacts to habitats—which depend on both physical and biological processes—could demonstrate the connection. White encouraged researchers to closely study area 522, near Nantucket Shoals, whose unique hydrography and large concentrations of birds and whales could be an optimal place to demonstrate this connection.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR COLLABORATION

To close the workshop, participants discussed opportunities for enhancing data-sharing and coordination and reflected on key areas of focus for guiding measurement strategies and improving models.

Data-Sharing and Coordination

Several participants emphasized that data-sharing and coordination are important elements in obtaining the information and insights for improving models and understanding potential impacts of wind energy development. Several attendees spoke to the role wind energy developers could play in facilitating data-sharing. Marsjanik stated that most developers, including Vineyard Wind, are already required to collect a large amount of meteorological and oceanographic data from lease areas via multiple tools. This creates opportunities for the data that companies are already collecting to be shared more widely, and for the platforms and instruments they are already deploying to be modified to collect additional data. If a buoy is already being deployed, for example, additional instruments can be added to it in order to more fully take advantage of that platform to fill data gaps. She suggested that greater collaboration between researchers and developers could help to enable such efforts. In addition, she noted that biological and oceanographic studies conducted during the permitting stage provide useful data on factors such as entrainment and cooling processes; data from these studies could also be shared more broadly, especially after a project is approved. She noted that developers would generally prefer to respond to a personal request to share data than a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, as there is a significant amount of data that is not considered confidential and processing requests through the FOIA mechanism comes with increased complexity. Ben Williams, Fugro, added that Atlantic Shores and SouthCoast Wind (formerly Mayflower) already publish and share much of their data, including data on precipitation, wind speed, wind direction, shear, current direction, velocity, and turbulence.

Williams also suggested that multiple stakeholders could work together to co-fund focused studies on zooplankton and right whale behavior in Nantucket Shoals. Orphanides suggested that greater coordination by groups such as the RWSC and, in particular, enhanced coordination around data access could be helpful moving forward; Kirincich, C. Chen, and Saba agreed. Morse suggested that ongoing collaborations on physical and biological oceanography in WEAs could be useful, and Nowacek added that there may be opportunities for RWSC and BOEM to provide input.

Kohut emphasized the importance of partnerships among the private, public, and academic sectors to implement ideas for field monitoring programs. Kritzer agreed, noting that partnerships are especially important for long-term large temporal and spatial scales. Given that multiple research groups are taking ocean

measurements for a variety of purposes, it makes more sense to share data than to repeat efforts. “Looking for partnerships beyond the focal themes of this workshop—where we can double and triple and quadruple dip with other ocean user needs—is going to help us achieve both spatial and temporal scale,” Kritzer said.

Guiding Measurement Strategies and Improving Models

Reflecting on various strategies for improving data collection that were raised during the workshop, several participants highlighted what they saw as key themes moving forward. Thorne, Kirincich, Orphanides, Saba, and Fratantoni agreed that concurrent biological and physical sampling across the ocean’s vertical structure is essential to understand the mechanistic links between key physical and biological processes, especially in the context of predator foraging. To advance this work, Saba suggested the combined use of fixed and mobile platforms, as well as discrete sampling, for understanding plankton species composition. Jim Chen suggested that a pilot study of concurrent physical and biological sampling at the turbine scale could be a useful starting place.

Differentiating the impacts of wind farms versus the impacts of other natural and anthropogenic factors is a significant challenge. Johnson emphasized the importance of considering the dynamic variability in the Nantucket Shoals area when attempting to isolate and identify wind farm effects. Kohut agreed, noting that context is important and reiterating that true “control” conditions are not feasible to obtain in the ocean. Kritzer agreed and underscored the urgency of establishing a baseline as soon as possible, as well as conducting WEA- and regional-scale monitoring over the life cycle of a project.

Several participants also highlighted specific research strategies and data collection opportunities that they see as particularly helpful. Carpenter suggested conducting process studies within long-term monitoring to focus on rapid timescales and small spatial scales. Williams added that it is important to keep track of ocean wakes, which are affected by boundary condition changes that should be included in models, on top of oceanographic and environmental changes. Leung stressed the importance of understanding the microstructure of near-field mixing. McSweeney emphasized the need for subsurface data and sampling at multiple resolutions and timescales to tease apart interacting processes in a dynamically evolving environment. Johnson suggested using scanning lidar at hub height and sea surface to better elucidate the transfer function. Nowacek added that remote sensors, such as NASA’s PACE satellite, could also provide useful data.

Williams highlighted several other data sources that could be leveraged to enhance field monitoring. For example, benthic habitat data can shed light on scour protection and monopile foundation changes; data on migratory species can help to reveal biological effects; and scientists could also leverage data generated from sensors connected to highly reliable supervisory control and data acquisition systems. In addition, he suggested that installing CTDs on fishing vessels could sup-

plement shellfish, cetacean, and scour studies and further enhance NOAA programs that equip vessels with visual observation tools for identifying and mapping species. Morse added that biological stock assessment and bottom temperature data can also supplement some of the long-term observational needs.

Mayo stressed the importance of working quickly to establish a baseline for both zooplankton and right whale activity in the area, and White suggested using nets vertically, eDNA, characterizing that very well is important and not described very well. Thompson said that new data and analysis tools are needed to predict environmental impacts in the context of the larger changes that are affecting the ocean and its high natural background variability. However, he noted, some studies could be accomplished with existing data and tools and often without requiring cumbersome FOIA requests; for example, he suggested that existing data could be leveraged to better understand how right whales’ foraging behavior might be changing in response to climate change. Morse similarly underscored the importance of delineating climate change impacts within these measurements and suggested establishing multiple stations to track whales and zooplankton advection. Marsjanik emphasized that, in whatever observational strategies are used, data collection tools and techniques be employed that avoid harm to animals, especially right whales.

Some participants also spoke to the possible mechanisms for informing and guiding future research and monitoring efforts. As a developer, Marsjanik said, it would be helpful to have a clear list of research questions, desired data, and perhaps “idealized” studies that could be done, which companies like hers could use to guide their investments. “What I would like to ask, before I even go for an RFP, is for a menu of options to clearly identify what those questions are that we’re asking,” she said. “Can we come up with a higher-level menu of options that BOEM, NOAA, and developers can react to and say, ‘This is a very important issue to us; we want to fund this?’”

Finally, several participants highlighted the interplay between observations and modeling, noting that, while enhanced observations are important to improve models, models can also be used to inform data collection efforts. Hofmann underscored the value of drawing upon a range of models, especially ones that can couple physics and biology, to guide measurements. Jim Chen agreed, noting that models can help to guide observations at both local and larger scales. Raghukumar emphasized the importance of improving models, suggesting that future measurements need to be taken in a way that the data can validate and calibrate models and generate more accurate output. “To answer this wind farm question, I think models are a really powerful way, possibly the only way, really, to come up with some kind of mechanistic understanding,” he said. “But the models at the moment—[we] have some work to be done in building confidence. I think that observations or any monitoring plan should be constructed in a way that it provides meaningful data for model validation and calibration, so that we can start to answer these mechanistic questions.”

This page intentionally left blank.