Climate Security in Central America: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

The impacts of climate change overseas pose a significant and cross-cutting threat to the security of the United States (NASEM, 2021; NIC, 2021a,b; USGCRP, 2018). Collectively, these impacts threaten critical natural and societal systems, undermine human health and well-being, and generate risks that can compound and cascade across societal sectors and borders (IPCC, 2022; O’Neill et al., 2022). Climate change increasingly drives food and water insecurity; illness and premature death; displacement and involuntary migration; and it is amplifying existing socioeconomic, political, and cultural drivers of instability and conflict (Cissé et al., 2022; IPCC, 2022). These impacts affect the security interests of the United States and its allies and partners by disrupting economic and trade linkages; undermining international development investments; and exacerbating geopolitical flashpoints (NIC, 2021b; USGCRP, 2018).

The U.S. Intelligence Community (IC) is responsible for providing policymakers with analyses and assessments that can illuminate threats to U.S. security. In its most recent Global Trends report, the National Intelligence Council framed climate change as a “shared global challenge” and one that is “likely to exacerbate food and water insecurity for poor countries, increase migration, precipitate new health challenges, and contribute to biodiversity losses” (NIC, 2021a). The most recent National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) states that climate change “will increasingly exacerbate risks to U.S. national security interests” (NIC, 2021b).

For more than a decade, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine have convened activities to explore the climate and security nexus. One such activity is the National Academies Climate Security Roundtable (CSRT or Roundtable), which was created at the direction of the U.S. Congress in 2021 and funded by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. The Roundtable leverages the unique convening power of the National Academies to create a platform for federal officials to engage experts from academia, the private sector, and civil society on a wide range of climate and national security issues (see Appendix A for more detail on the Roundtable and its work).

The Climate Security in Central America workshop summarized in this proceedings was convened under the auspices of the CSRT. The workshop’s overarching goal was to advance an integrative systems understanding of climate security risk in Central America and to identify examples of the basic analytic capacities and capabilities that could support a more integrative analysis of climate security in the region. This introductory chapter explains the motivation behind the selection of Central America as the regional focus, summarizes the opening remarks of the workshop’s keynote speaker, presents some relevant perspectives on climate security analysis from the Roundtable’s previous discussions, and describes the basic organization of the workshop and this proceedings.

MOTIVATION FOR THE WORKSHOP

The Central America region—comprising Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama (see Figure 1-1)—presents a unique confluence of major climate hazards and key U.S. security concerns. The preparatory materials for the workshop, along with remarks in the opening sessions, explained the reasoning behind the Roundtable’s choice to focus on Central America:

- From a demographic and socioeconomic standpoint: Central America is a region facing profound social and economic challenges (see Box 2-1 in Chapter 2). It is a relatively small but densely populated region; its size and generally low levels of socioeconomic development have led to individual national economies that are also quite small and have

- From a weather and climate standpoint: Central America experiences a wide range of hazards, including tropical cyclones and other extreme weather events, that have upended the lives and livelihoods of millions of people. In the coming years, climate change is expected to increasingly expose people and society to adverse effects. Projected impacts include increased heat stress, increased agricultural losses, decreased water availability, increased climate-sensitive infectious diseases, and degradation of regional ecosystems. These impacts could push people into deeper poverty, increase food and water insecurity, and exacerbate already intense migration pressures (see Box 2-2 in Chapter 2). The resulting human and economic losses could disrupt social structure and cohesion, weaken governance, and further increase the risks of crime and violence.

faced challenges in terms of poverty and integration into the global economy. While two countries in the region—Panama and Costa Rica—have been positive outliers with strong and modern economies, the region is characterized by generally high levels of poverty and economic, ethnic, and gender inequality. Two countries—Nicaragua and Honduras—are among the poorest in the Western Hemisphere. High rates of political corruption mean that democratic institutions often do not function properly; basic public service provision can be ineffective; and laws and regulations, particularly those related to land use and natural resource management, are enforced irregularly (Ruhl, 2011). In such a setting, vulnerability to global climate change is exacerbated.

- From a security standpoint: Central America is the setting for a range of social and political dynamics that impact U.S. interests (see Box 2-3 in Chapter 2). The recent U.S. NIE on climate change identified Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua as countries “of great concern from the threat of climate change” (NIC, 2021b). Criminal activity exploits weak governance across the majority of Central American countries, and transnational criminal organizations operating in the region threaten U.S. security through their trafficking of drugs, people, wildlife, and weapons. Outward migration from the region into North America is a critical issue for the United States. In recent years, the countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras (the “Northern Triangle”) have experienced an exodus of people in response to a lack of economic opportunity, chronic violence, and environmental stressors. In addition, geopolitical issues and tensions have a strong imprint on the region. A key U.S. interest in Central America is the Panama Canal, which is a critical node in global trade and supply chains and is increasingly stressed by climate change. Extra-regional actors also have a presence in the region. China seeks to increase its economic and security influence, as well as to apply political pressure on countries to derecognize Taiwan. Russia’s primary involvement in the region has been in Nicaragua, although its influence seems limited currently.

KEYNOTE ADDRESS FROM THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

In a keynote address, Iris A. Ferguson, deputy assistant secretary of Arctic and global resilience at the Department of Defense (DoD), provided additional perspective on the U.S. national security community’s approach to climate challenges. She explained that DoD has established the Office of Arctic and Global Resilience to comprehensively integrate climate change considerations into all aspects of DoD operations and planning. This commitment stems from high-level guidance from documents such as the National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy, which frame climate change as a cross-cutting, transboundary challenge that is fundamentally reshaping the geostrategic environment in which DoD and the U.S. government must operate. Ferguson elaborated on numerous DoD efforts already underway to enhance the resilience of its bases and installations worldwide; to develop more fuel-efficient and climate-resilient military platforms; and to build climate resilience among allies and partners globally, including helping countries adapt to mounting climate impacts.

In the Western Hemisphere specifically, Ferguson noted that countries are experiencing growing climate impacts from extreme heat, water cycle extremes, storms, and sea level rise, which exacerbate existing resource stresses and instability. She highlighted the outsized role that national militaries play in humanitarian assistance and disaster response in the region, citing the critical emergency response assistance that DoD has provided in the Caribbean after recent devastating hurricanes. In addition, she noted the extensive U.S. wargaming exercises conducted last year in relation to anticipated second-order climate impacts over the next 10–15 years, including potential mass migration events and civil unrest stemming from climate-exacerbated resource stresses.

Ferguson emphasized the critical importance of accurate, up-to-date climate information to inform DoD decision-making on a range of timescales. DoD currently utilizes an array of tools, including long-term installation exposure projections out to 2050–2085 and advanced assessments of climate impacts on regional food–water–energy security. Ferguson noted that an important gap in DoD’s current climate projection capabilities lies in the 1-to-10-year time horizon, which is vital for near-term defense planning, posture adjustments, and operational preparedness. Advancing climate projection research focused on the 1-to-10-year time frame could substantially improve DoD’s strategic foresight, battlespace awareness, and proactive global climate resilience efforts.

In response to a question on how to facilitate greater collaboration between the national security and climate research communities, Ferguson noted the need for increased data sharing

and exchange of analytical methods, as well as better integration of the latest climate science insights into intelligence assessments. She argued that, despite the institutional sensitivities that may exist, building partnerships between climate researchers and intelligence officers and increasing awareness among climate researchers of key intelligence gaps are urgent priorities. In response to a question on how to establish climate as an enduring national security priority across political cycles, Ferguson highlighted the need to strengthen cross-agency collaboration, effectively convey insights to policymakers, and mainstream climate risks into everyday security discourse. She noted that DoD’s new monthly intelligence brief compiles climate inputs from across the IC.

In closing, Ferguson reiterated that DoD is taking steps to address escalating climate change risks; she noted that these efforts require thoughtful collaboration with a range of experts in academia, the private sector, civil society, and government. She expressed confidence that insights gained from activities such as this workshop would deepen DoD’s evolving understanding of the multifaceted climate risks facing Central America and of potential collaborative approaches to strengthen regional climate resilience.

KEY PERSPECTIVES FROM THE CLIMATE SECURITY ROUNDTABLE

A central aim of the CSRT’s work has been to advance an integrative understanding of climate-related security risk—one that considers the diverse interactions between nature and society and illuminates the pathways along which climate-related security risks can evolve. To help participants organize their discussions at the Central America workshop, the co-chairs and staff of the Roundtable summarized some of the key themes that have emerged from its previous discussions, including perspectives on systems approaches to climate security, conceptualization of complex risks, and the human dimensions of security1:

- The importance of a systems approach: The term systems thinking does not currently have a precise, agreed-upon definition. In the context of climate change, however, systems thinking generally recognizes that the complex and unpredictable nature of climate risk arises from the deep interconnections and interdependencies that exist both within and between the natural and societal components of the world, at all scales. Specifically, a systems approach to climate-related risks would consider the dynamic interactions and feedbacks between social, economic, political, and environmental factors that create the potential of harm to people and nature. A systems framework for climate security analysis considers the particular human and natural geographic setting for the analysis, the influencing factors acting from outside of that setting, and the networked interactions of systems within the analytic setting (see Figure 1-2). This approach is influenced by a multisectoral dynamics (MSD) perspective, which provides a useful approach to the various interactions and feedbacks between nature and society that produce security risks. MSD considers nature and society as systems of systems that are interconnected, interdependent, and coevolving in relation to a set of dynamic influences and stressors (Reed et al., 2022).

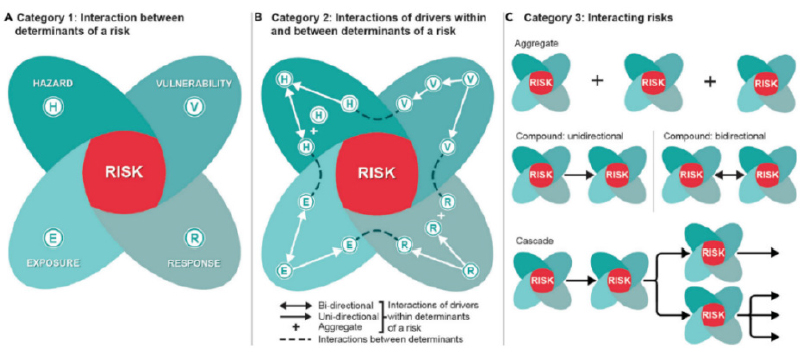

- Conceptualizing complex risk: A useful conceptualization of risk is that it emerges from the dynamic interplay of several determining factors: hazards, exposure, and vulnerability, as well as the human responses that can modulate them (see Figure 1-3). The complex behavior of climate risk arises from interactions at multiple scales: the interplay of factors within a single risk determinant; the overlap between different determinants; and the aggregating, compounding, or cascading interactions between separate risks

___________________

1 This summary presents some key themes from previous discussions between CSRT members. It does not provide a comprehensive summary of these discussions and does not reflect a consensus view of the Roundtable or of the National Academies.

- Incorporating the human dimensions of security: Security is not simply the absence of conflict and instability; it is fundamentally grounded in the health and well-being of individuals, communities, and societies. The national security implications of climate change are thus profoundly determined by the interplay between climate and society. Understanding these climate–society interactions involves a deep exploration of human motivations and behavior across scales.

(Reisinger et al., 2020; Simpson et al., 2021). Importantly, risk arises from both the physical impacts of climate change and the human responses to climate change.

SOURCE: Generated by the Climate Security Roundtable.

ORGANIZATION OF THE WORKSHOP AND PROCEEDINGS

The National Academies hosted the workshop Climate Security in Central America on May 3–4, 2023, at the National Academy of Sciences building in Washington, DC, and virtually. The workshop was held under the auspices of the Climate Security Roundtable and was organized by a planning committee of Roundtable members and external experts tasked with designing the agenda and identifying speakers (see Box 1-1). Over the course of two days, participants engaged with invited speakers in panel sessions and with each other in plenary and small-group discussions to explore the climate and security landscape in Central America, examine indicators and pathways for climate-related security risks in the region, and consider the data and tools that may be useful to assess and anticipate those risks.

The Central America climate security landscape encompasses a broad range of issues and challenges. To avoid an unfocused analysis, the workshop began by defining specific risks upfront.

The subsequent discussion was structured into three key sections, examining (1) Indicators, (2) Pathways, and (3) Data and Tools. In the Indicators section, participants discussed metrics, as well as variables that could serve as metrics, for important climate-related security risks affecting Central America. In the Pathways section, participants envisioned plausible sequences of events over the coming years that could lead to dangerous climate security risk levels, based on the indicators identified earlier. In the Data and Tools section, participants highlighted the analytical capabilities and tools that could help to adequately assess Central America’s climate security risks.

SOURCE: Simpson et al. (2021).

This proceedings summarizes the discussions at the workshop and is organized to reflect the major themes explored over the 2 days. Following this Introduction, Chapter 2 sets the stage by describing the underlying human and natural geographic setting of Central America, as well as the key climate and security risks in the region. Chapter 3 explores climate security indicators. Chapter 4 considers potential futures for climate security. Chapter 5 considers the current tools for analyzing and forecasting climate-related risks.