Exploring Sanctions and Early Interventions for Faculty Sexual Harassment in Higher Education: Issue Paper (2022)

Chapter: Exploring Sanctions and Early Interventions for Sexual Harassment Perpetrated by Faculty in Higher Education

![]() PERSPECTIVES

PERSPECTIVES

Exploring Sanctions and Early Interventions for Faculty Sexual Harassment in Higher Education

Authored by members of the Response Working Group from the Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education1

This perspective paper is a product of the Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. It is intended to identify and discuss a topic in need of research. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily of the authors’ organizations or the Action Collaborative, nor do they represent formal consensus positions of the National Academies. Copyright by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Learn more: http://www.nationalacademies.org/sexualharassmentcollaborative

__________________

1 Information about the authors can be found at the end of the paper.

Introduction

Faculty sexual harassment is a widespread problem in higher education. A survey conducted at 27 top research universities reported that 5.9 percent of female undergraduates and 22.4 percent of female graduate students reported sexual harassment by a faculty member (Cantor et al., 2015). Another study surveying 525 graduate students reported that 38 percent of women and 23.4 percent of men experienced sexual harassment from faculty/staff (Rosenthal et al., 2016). A systematic review of 305 cases of faculty–student harassment found that more than half involved (1) unwelcome physical contact (i.e., groping, sexual assault) and (2) repeat offenses by the same faculty member (Cantalupo and Kidder, 2018). The consequences of sexual harassment, including gender harassment, can be severe and wide ranging. Examples include decreased mental health and well-being (e.g., posttraumatic stress symptoms), education limitations (e.g., decreased participation in lab spaces or courses), and disruption to academic career advancement (e.g., losing professional development or funding opportunities through advising relationships, having to pursue a different discipline/medical specialty, being concerned about tenure prospects) (Cipriano et al., 2021; NASEM, 2018; Nelson et al., 2017; Rosenthal et al., 2016; Stratton et al., 2005).

Although sexual harassment by faculty is prevalent, sanctioning or other early intervention responses are often hindered by characteristics of higher education, such as “academic star culture,” the power differentials perpetuated by academic hierarchal systems, and the strong due process protections provided by tenure system and other faculty governance structures. Another barrier to responding is the underreporting of sexual harassment by harmed parties because of concerns related to (1) retaliation, (2) disruption of their own or the faculty member’s academic career, and (3) convoluted university systems or processes for handling sexual harassment (Curtis, 2017; NASEM, 2018; Pappas et al., 2021; Weiner, 2018).

The Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine brings together academic and research institutions and key stakeholders to work toward targeted, collective action on addressing and preventing sexual harassment across all disciplines and among all people in higher education. The Action Collaborative includes four working groups (on Prevention, Response, Remediation, and Evaluation) that identify topics in need of research, gather information, and publish resources for the higher education community. Members of the Response Working Group decided to explore the challenges and research areas related to responses to faculty sexual harassment (e.g., progressive disciplinary sanctions and early interventions) discussed in the 2018 National Academies report Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Research demonstrates that appropriate and effective institutional responses to faculty sexual harassment and transparency in those responses are critical for building an organizational climate that is demonstrably intolerant of sexual harassment; works to prevent that behavior; and seeks to reduce experiences of institutional betrayal, or “the general perception that institutions are unable or fail to prevent or respond supportively to wrongdoings by individuals” (NASEM, 2018, p. 137; see also Cantalupo and Kidder, 2019; Smith and Freyd, 2014).

__________________

2 “Academic star culture refers to the beliefs or assumptions that well-known academics on campus who command significant resources can operate without ordinary rules being applied to them” (NASEM, 2018, p. 130).

Key Points from 2018 Sexual Harassment of Women Report

The report highlights that “progressive discipline (such as counseling, changes in work responsibilities, reductions in pay/benefits, and suspension or dismissal) that corresponds to the severity and frequency of the misconduct has the potential of correcting behavior before it escalates and without significantly disrupting an academic program” (NASEM, 2018, p. 144). The report also notes that using such a range of disciplinary actions may increase the likelihood that the harmed parties (i.e., individuals impacted by the sexual harassment) will report the incident since they often choose not to do so because they fear disrupting the status quo and their own or other people’s academic career. The report suggests that “disciplinary sanctions may be best determined based upon a review of the circumstances on a case-by-case basis” and that examples of which behaviors would warrant which disciplinary actions could help improve transparency (NASEM, 2018, p. 144). In addition to progressive disciplinary actions, the report suggests it may be appropriate for institutions to consider actions beyond sanctions (i.e., rehabilitation-focused measures or restorative justice procedures), as such actions may both change behavior and improve the organizational climate (NASEM, 2018).

Purpose of This Paper

Many colleges and universities in the United States lack clear guidance on available sanctions for faculty found responsible for sexual harassment or other early interventions for faculty accused of sexual harassment. (See Box 1 for definitions of sexual harassment and other key terms used in this paper.) Faculty disciplinary processes for determining findings of responsibility for sexual harassment and issue sanctions are typically based on either investigation or hearing models3 (Pappas, 2018). Responsibility for imposing a sanction often falls to an academic administrator—a provost, dean, or academic vice president—who has had little or no formal training in this area and for whom each situation may be a unique event. Most academic administrators are aware of termination as a sanctioning option for cases that involve sexual assault or coercion, or pervasive sexual harassment that occurs repeatedly over years. However, it is difficult to find information on what sanctions might be appropriate for gender-harassing behaviors (which are often perceived to be less severe, though can have the same professional and psychological consequences as sexual coercion4 [NASEM, 2018]) because of the lack of transparency in higher education institutions’ responses to such harassment. Indeed, lack of transparency can be a problem even within a single institution. In addition, beyond formal complaints, sexual harassment can be reported or disclosed informally, and the processes for handling those situations are often not clear for institutional or departmental academic administrators (e.g., dean, provost, department chair) and institutional staff. In particular, we note that the ways in which academic administrators may intervene and hold tenured or tenure-track faculty accountable for harmful behaviors that are not deemed institutional or legal violations are not well-known or codified, or may not even exist at the institutional level. Yet these processes are often crucial for attending to misconduct before it rises to the level of a violation of institutional policies or federal or state laws.5

__________________

3 In the investigation model, an administrator(s) conduct(s) an investigation to determine findings of responsibility and issues sanctions. The faculty member found responsible can appeal the sanctioning decision to a faculty grievance committee. In the hearing model, an investigation is conducted before being presented to a faculty hearing panel who determines if there was a policy violation and recommends a sanction. A higher-level academic administrator then issues the final sanctioning decision (Pappas, 2018).

4 A recent study focused on graduate students demonstrates that gender-harassing behaviors often perceived to be less severe by Title IX practitioners can lead to “severe, education-limiting consequences” (Cipriano et al., 2021).

5 These early interventions are also relevant given recent studies highlighting the prevalence of faculty members with repeat offenses of sexual harassment in higher education institutions (Cantalupo and Kidder, 2018; Flaherty, 2017).

BOX 1

DEFINITIONS OF KEY TERMS USED IN THIS PAPER

- Sexual harassment: behaviors defined in the 2018 National Academies report as “(1) gender harassment (verbal and nonverbal behaviors that convey hostility, objectification, exclusion, or second-class status about members of one gender), (2) unwanted sexual attention (verbal or physical unwelcome sexual advances, which can include assault), and (3) sexual coercion (when favorable professional or educational treatment is conditioned on sexual activity)” (NASEM, 2018, p. 170). This definition does not specify which behaviors are legal violations, as doing so often requires consideration of the specific case details. Sexual misconduct is another term used to refer to these behaviors; however, to our knowledge, there is no research-based or legal definition for this term and the specific range of behaviors it includes.

- Harmed party: individual(s) who have been impacted by a faculty member’s sexually harassing behaviors. This term is also used to refer to those who have filed a formal complaint and are referred to as complainants in legal terms. Harmed party(ies) can include any member of the higher education institution (e.g., student, postdoctoral researcher, faculty member, or institutional staff member).

- Academic administrator: higher education employee, typically a current or former faculty member, with leadership and administrative responsibilities at the departmental level (i.e., department chair) or institutional level (e.g., provost, dean, faculty senate member).

- Accused faculty member: faculty member (i.e., an educator who works at an institution of higher education) accused of sexual harassment or a related institutional policy violation (i.e. retaliation or unprofessional conduct) through an informal disclosure or a formal complaint (i.e., a respondent in legal terms). Faculty members can encompass tenure-track, tenured, or non-tenure-track/contingent/adjunct faculty; however, this paper focuses on challenges in responding to sexual harassment by tenure-track and tenured faculty.

- Faculty member found responsible for sexual harassment: faculty member found responsible through a formal investigation process for having committed sexual harassment.

- Sanctions: formal disciplinary actions imposed following a formal investigation and finding of responsibility, such as suspension, salary reduction, demotion, removal of privileges, or termination of employment (Cantalupo and Kidder, 2019).

- Early interventions: responsive actions (e.g., corrective, rehabilitative, restorative, or monitoring measures) designed to (1) correct the harmful, sexually harassing behaviors by the accused faculty member before they rise to the level of a policy violation and (2) address the harm caused to the harmed party.

The aim of this paper is to galvanize the much-needed research on responding to sexual harassment by tenured and tenure-track faculty, as these efforts are most challenging because of the power differentials perpetuated by academic hierarchal systems and the strong due process protections provided by the tenure system and other faculty governance structures. To this end, the paper (1) describes the landscape of higher education response systems for sexual harassment, including both formal sanctions for faculty found responsible for sexual harassment following an institutional finding of a policy violation, as well as less formal early interventions designed to address and correct behaviors of accused faculty before they rise to the level of a policy violation; (2) highlights existing challenges that arise in the processes for determining and enforcing appropriate sanctions or

early interventions to hold faculty accountable; and (3) identifies areas of research needed to improve all processes used for responding to faculty sexual harassment. While this paper focuses on challenges in responding to sexual harassment by tenure-track and tenured faculty, we acknowledge there are other underexplored challenges, including: (1) responses to harassment by non-tenure-track faculty (e.g., adjunct/temporary or part-time instructors), who are beginning to outnumber tenure-track faculty at many universities, and (2) variations in responses depending on the career stage and/or appointment type of the harmed party. Thus, we have included questions for exploring these issues in the research agenda at the end of this paper.

The challenges discussed here were contributed by the authors, who represent a range of stakeholders and actors within the higher education community, including Title IX officers and coordinators, academic administrators, university ombuds, sexual assault prevention and education program leaders, and faculty members. We believe that addressing these challenges, starting with the institutional members of the Action Collaborative and then expanding beyond, will not only be of service to individual faculty and academic administrators, but also assist in creating the changes in organizational climate essential to preventing both sexual harassment and experiences of institutional betrayal (Cantalupo and Kidder, 2019; Flaherty, 2019; Smith and Freyd, 2014).

The Landscape of Higher Education Response Systems for Faculty Sexual Harassment

The landscape of higher education response systems designed for faculty sexual harassment is complex and multifaceted, involving any or all of the following: Title IX offices, human resources, student affairs, law enforcement, confidential resources, academic administrators, and offices of general counsel. Because different institutional policies and state and federal laws may govern each of these entities’ work within the institution, coordinating a response to sexual harassment among and between them can be challenging. Large institutions encompassing several schools, health systems, and numerous other entities may also face the challenge of a lack of consistency in response policies, processes, and practices across the institution.

Frequently Changing Standards

Institutional policies for sexual harassment response are developed to comply with federal Title IX rules and requirements, and many institutions expand upon these requirements to develop policies that are even more robust. However, adhering to Title IX rules and regulations, governed by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights is challenging as Title IX policies can shift with each administration (Camera, 2021; Pappas, 2021a; Quilantan, 2022). Many institutions struggle to adapt to the wavering Title IX regulations (Brown, 2015), exacerbating the challenges of promoting coordination and consistency in their responses to faculty sexual harassment (Pappas, 2021b). Relatedly, shifting regulations may also complicate responses to faculty sexual harassment when they conflict with faculty disciplinary processes designed to protect their due process rights, especially for tenured faculty (e.g., differences in evidentiary standards used and limitations in campus procedures for supporting rights to confrontation) (AAUP, 2016; Pappas, 2018).

Confidentiality in Facilitating Reporting and Response

The nature of the sexual harassment reported typically dictates an institution’s response, which may vary based on the position of the accused faculty member in relation to the harmed party; the behavior in question, regardless of the type of report submitted (formal complaint or informal disclosure); and the wishes and needs of the harmed party. Institutions strive to respect

the harmed party’s preference with respect to anonymity or confidentiality; in some instances, however, they must investigate to comply with Title IX because failure to do so could result in violating state or federal law (Pappas, 2016). For example, institutions may have to investigate allegations of sexual harassment that are severe, persistent, and pervasive or allegations of sexual assault when failing to do so could render the institution “deliberately indifferent” by Title IX standards![]() 6 and liable by Title VII standards. Institutions also have to balance a desire to provide confidentiality with legal requirements for those obligated to report to an institution’s Title IX office. While there is flexibility in who and what roles an institution determines are required to report incidents of harassment, many institutions take an all-inclusive approach that can remove confidentiality and control for harmed parties (Holland et al., 2021; Weiner, 2018).

6 and liable by Title VII standards. Institutions also have to balance a desire to provide confidentiality with legal requirements for those obligated to report to an institution’s Title IX office. While there is flexibility in who and what roles an institution determines are required to report incidents of harassment, many institutions take an all-inclusive approach that can remove confidentiality and control for harmed parties (Holland et al., 2021; Weiner, 2018).

In addition to the formal institutional response system administered by Title IX administrators that cannot guarantee confidentiality, institutions often also have resources or offices on campus that can provide confidential support to the harmed party—these include ombuds, advocates, and counselors. Specifically, ombuds can “explain the processes and procedures involved and allow individuals to have an open conversation about options without being required to make an official report” (Pappas et al., 2021, p. 763; see also Pappas, 2016), and they can assist with systemic improvements in an institution and share aggregate information about individuals’ concerns and common issues while maintaining anonymity (Pappas, 2021b; Pappas et al., 2021). While these confidential institutional resources are able to provide various means of support, some of which can assist leaders and harmed parties in figuring out their options for proceeding, these confidential services are not able to provide investigation, adjudication, sanctions, interventions, or alternative dispute resolution in response to the harassment that is shared with them (Pappas et al., 2021). This separation of roles for confidential and nonconfidential resources is necessary to comply with state and federal laws and to provide harmed parties with options and services that ultimately result in an increase in formal reports; however research suggests that this separation becomes blurred at times (Pappas, 2016; Pappas et al., 2021).

Overlapping Formal and Informal Reporting and Response Systems

Overlap is also common between the formal and informal response systems that provide confidentiality. Informal response systems are an important alternative to formal response systems; they provide valuable options for harmed parties with different wishes (e.g., those who want to remain anonymous or do not wish to proceed with a formal investigation that could be retraumatizing) and/or various situations making it difficult to proceed with the formal process (e.g., the situation/behavior does not meet the standard of a policy violation but is causing harm and could escalate if not addressed) (Pappas, 2021b). The formal and informal response processes can overlap as Title IX administrators and ombuds adapt to shifting Title IX regulations and attempt to shape their processes to better support harmed parties and hold accused faculty accountable (Pappas, 2021b). However, researchers underscore the importance of separating the formal and informal processes to ensure there are clear and meaningful response options for harmed parties (Orcutt et al., 2020; Pappas, 2021b; Pappas et al., 2021).

An institution’s response system is designed to address sexual harassment policy violations through sanctions, and can do so only after a formal investigation and finding of responsibility

__________________

6 This paper is based on the Title IX regulations released in 2020 by the Department of Education (DOE, 2020). The authors are aware that the Department of Education has proposed new regulations in June 2022, which could alter considerations of the issues discussed in this paper.

to align with due process requirements (DOE, 2020). Although institutional response systems are designed to address policy violations following formal findings of responsibility, subsequent efforts to sanction faculty found responsible for sexual harassment are complex and lengthy, and can result in no sanction even when warranted. Implementing faculty sanctions can be challenging because of the power differentials perpetuated by academic hierarchal systems (which can affect faculty-led disciplinary proceedings), the strong and prolonged due process protections provided by the tenure system and other faculty governance structures (e.g. tenure system, faculty union contracts/collective bargaining agreements, faculty handbooks), and the frequency of lawsuits filed to dispute findings of responsibility (Brown, 2015; Brown and Mangan, 2019; Euben and Lee, 2005a; Euben and Lee, 2005b; Kingkade, 2017a; Kingkade, 2017b; NASEM, 2018; Pappas, 2018).

Underdeveloped Systems for Early Intervention

When alleged conduct by an accused faculty member is inappropriate but may not represent a violation of university policy, institutions are less equipped to respond. The swinging pendulum of Title IX standards impacts this issue directly, as it can narrow what behaviors constitute actionable sexual harassment (e.g., the shift in using the “severe or pervasive” to the “severe and pervasive” standard in the 2020 Title IX regulations [DOE, 2020]) (Pappas, 2021b). For example, Title IX administrators are less likely to deem gender harassment as actionable using the severe and pervasive standard, even when it has been shown to have severe and pervasive impacts on a harmed party’s access to educational programs or activities (Cipriano et al., 2021).

A significant number of institutions lack systems or processes designed explicitly to respond to reports of faculty sexual harassment that would likely not constitute a violation of the institution’s policies, or state or federal law. Examples include reports of such forms of inappropriate conduct as asking a student or colleague about their sex life, offering occasional comments about their attire, or making infrequent sexual jokes. If such behavior is left unaddressed, however, the accused faculty member may be emboldened to continue or even escalate such sexually harassing behaviors, increasing harm to the harmed party and other members of the institutional community. The lack of a response can also elevate feelings of institutional betrayal and discourage those who have experienced harm from reporting it (Bergman et al., 2002; Clarke, 2014; Jacobson and Eaton, 2018; Johnson et al., 2016; Knapp et al., 1997; NASEM, 2018).

Indeed, some institutions lack a system for addressing faculty misconduct generally. Unlike other employees who are accountable to a supervisor or manager with regard to their performance and conduct, many faculty are not subject to the same level of oversight. Relatedly, faculty in departmental leadership roles responsible for faculty oversight (e.g., department chairs) may feel conflicted about taking corrective action towards another faculty member that they consider to be a peer. A further complication is that some institutions may lack appropriately trained professionals (individuals who are trauma-informed and understand the local departmental structures and climate) in academic departments who can guide academic administrators on proper responses to misconduct.

Given these limitations, many individual departments and/or units in higher education institutions may respond with informal responses (i.e., early interventions) to informal disclosures of harmful sexual behavior by accused faculty members that may not meet the threshold for formal disciplinary action. We believe the intent of such early interventions is to provide measures to encourage behavior change to address what the department or unit may identify as a limited-impact “mistake” or a result of “ignorance.” In

our collective experience, early interventions may include, but need not be limited to, direct conversations with the individual reported to have caused harm, casual “coffee” conversations providing behavioral guidance or feedback (see Appendix A), informal social norming explanations of departmental culture or behavioral expectations, or imposition of a temporary hiatus from specific committees or involvement in areas of increased risk (e.g., graduate student oversight, conference attendance).

We see such early interventions as working in parallel with, not as replacing, formal documentation, required reporting to a Title IX office, and disciplinary action for behaviors that may violate institutional policies. If early intervention does not correct the harmful behavior (if the behavior becomes pervasive and/or escalates), it may be appropriate to transition to a formal response process. Without procedures for properly documenting and tracking repeated and/or escalating sexually harassing behaviors, early interventions could inadvertently allow those harmful behaviors to be minimized, absolved, or concealed (Harvard University, 2021; Pappas, 2021b). Implementing early interventions in the absence of procedures for documentation or pattern tracking may facilitate perceptions of institutional betrayal (Smith and Freyd, 2014). Additionally, we acknowledge that any approaches for implementing early interventions will need to be aligned with and take into account an institution’s policies on mandatory reporting.

Current Challenges in Higher Education for Responding to Faculty Sexual Harassment

Lack of Coordination in Documenting Faculty Sexual Harassment

As noted previously, at many institutions, multiple entities (individuals and offices) are involved in receiving and handling reports of sexual harassment; however, their effectiveness is often diminished by a lack of coordination of their efforts and competition or conflict between offices (Pappas, 2021a). The decentralized processes for receiving and documenting both formal complaints and informal disclosures of sexual harassment can result in outdated, inaccurate, and incomplete records for faculty accused of or responsible for sexual harassment (Tepper and White, 2011). A recent report on sexual harassment at Harvard University, for example, states that multiple disclosures of a faculty member’s sexual harassment over many years were divided between two separate offices that did not communicate with each other (Harvard University, 2021). The incomplete records of the faculty member’s repeated offenses in both offices led to an ineffective disciplinary response and an inability to enforce disciplinary actions that were deemed appropriate.

Some institutions also lack centralized mechanisms (e.g., shared software or hotspot mapping) for documenting and tracking reports on faculty accused of or found responsible for sexual harassment, further inhibiting effective responses. Based on our professional experiences, many institutions fail to maintain personnel files for faculty members in the way that may exist for administrative staff. The human resources office may have “official” faculty personnel files with minimal information on appointment, salary increases, and so on, but they do not include information from other files in departmental and deans’ offices (e.g., letters of commendation or complaint, documentation of disciplinary actions taken). Further, individual chairs, deans, or provosts may maintain their own “private” files documenting difficult conversations with problematic faculty. Thus, there may be no one source that thoroughly and consistently documents reports of a faculty member’s sexual harassment or other misconduct. Indeed, in some cases, instances of sexual harassment that are disclosed informally may not be documented in any record at all. Another, related

issue is that faculty leaders may not be accustomed to consulting personnel files or institutional records (e.g., records from Title IX offices) on the faculty members within their purview, which if accessed might enable them to form a complete picture of previous or repeat occurrences of faculty sexual harassment.

Even when an institution does provide a centralized office or mechanism for tracking reports of harassment by individual faculty members so that all such reports are accessible in one location, cases or incidents may not always be reported to that office. There may be a lack of clarity regarding how egregious an incident needs to be to rise to the level at which it should be reported. Faculty and staff may also be unaware of what office should receive reports of such incidents, and may even lack knowledge of their obligation to report. Chairs or other faculty may decide to handle such incidents “in house” and not involve the central administration. There may also be a lack of broader institutional trust in the central office that handles such complaints, with concern that harmed parties may be retraumatized by that office if investigatory personnel are not trauma-informed or trauma-trained. Additionally, structural challenges with how the centralized office is set up can also limit its effectiveness in coordinating. For instance, the staff within a Title IX office often lack the positional or political authority within the institution’s hierarchy and have insufficient resources (i.e., minimal financial support, low staffing levels, conflicting institutional goals) to achieve the substantial coordination that is required at large, diffuse institutions. Further complicating the need for coordination by Title IX officers is a high turnover rate, meaning that institutions are losing institutional knowledge and familiarity that are beneficial for coordination (Pappas, 2021a).

The lack of sexual harassment documentation also poses a problem when academic administrators (department deans or chairs) transition out of their leadership roles or an office is restructured, as they may be the only individuals in their department or school who is privy to informal disclosures of a faculty member’s sexual harassment. And as multiple reports on sexual harassment demonstrate, relying on a “whisper network” to provide continuity between leadership transitions is not effective in enforcing sanctions and protecting community members (Harvard University, 2021; Hill, 2018). Absent coordinated documentation of information in faculty personnel files to provide continuity between academic administrators, we are concerned that institutions could potentially contribute to the problem of “passing the harasser”—whereby a faculty member accused of or found responsible for sexual harassment transitions to another position without the new employer having any record of the person’s previous misconduct—either within a single institution, within a university system, or across higher education institutions (Cantalupo, 2019; Jain et al., 2021; Salazar, 2021). Recent examples include (1) a football coach who was hired at the University of Kansas despite allegations of sexual misconduct during previous employment at Louisiana State University (Russo, 2021) and (2) an accused faculty member who moved from the University of Wisconsin–Oshkosh to the University of Colorado Boulder while in the midst of a sexual harassment lawsuit (St. Amor, 2019). Although passing the harasser is widespread in higher education, recent policy efforts to improve coordination and transparency by higher education institutions (Harton and Benya, 2022a,b) and federal agencies (Tabak, 2022) aim to prevent it.

Lack of Transparency in Responses to Faculty Sexual Harassment

Transparency around how an institution handles reports of faculty sexual harassment is critical for cultivating a campus climate that is widely considered intolerant of sexual harassment. Institutions can build an organizational climate that resists and prevents sexual harassment by, at a

minimum, being transparent about (1) the extent or prevalence of sexual harassment in the institution; (2) the patterns of harassment (e.g., whether some individuals are more likely than others to be subject to harm based on race, status, rank, or discipline); or (3) whether the shared understandings within the institution regarding how sexual harassment should be handled are informed by the scholarly research on gender, sexism, and power in organizations (NASEM, 2018).

While transparency has proven to be important for fostering a positive organizational climate, many institutions are not transparent about their faculty sexual harassment investigations and sanctions because of potential legal concerns (i.e., defamation lawsuits and privacy violations [Brown and Mangan, 2019; Leatherman, 1996]); however, we note resources that suggest there are protections for employers that mitigate these concerns (see Harton and Benya, 2022a; Schlavensky, 2019; UW System, 2019). Beyond these legal concerns, we have observed that institutions often must weigh a variety of factors when considering the appropriate level of transparency (what information and the amount of detail to share) with the harmed party, members of the institutional unit (department/laboratory/center) who may be aware of the allegations, and the broader institutional community. These factors include employees’ rights to privacy and discretion (for both the harmed party and the faculty found responsible), the purpose for sharing the information (e.g., community safety and sanction enforcement), differing requests for privacy by harmed parties, and the potential impact on the reintegration of rehabilitated faculty. In addition to federal laws and regulations, specific requirements imposed by state laws, contractual legal agreements (e.g., collective bargaining agreements), federal funding agencies, and professional societies may influence the consideration of these factors. One particularly important but challenging factor is how to respect the wishes of the harmed or reporting party. For some harmed parties the prospect of transparency, even after a finding of responsibility is made, may discourage them from reporting because they fear reprisal from the accused faculty member or their peers, or don’t want to be responsible for “ruining someone’s career” and primarily want the behavior to stop (NASEM 2018; Pappas, 2016; Pappas et al., 2021). However not all harmed parties feel this way, and some want others to be aware and warned about the accused faculty member’s behavior and that the institution found them responsible (Freyd, 2018; NASEM 2018).

Despite these considerations, however, nontransparent practices can leave community members at risk, especially in cases of serial harassers (Nayak and Springs, 2019). Research shows that nontransparent practices can discourage reporting by harmed parties, who fear the institution will respond inadequately to their concerns and therefore feel subject to institutional betrayal (Aguilar and Baek, 2020; Freyd and Birrell, 2013; Harvard University, 2021; Widener and Wang, 2021). Furthermore, an institution’s failure to acknowledge publicly that a faculty member has been sanctioned can communicate to the community implicitly that sexual harassment is not taken seriously, and potentially embolden faculty found responsible for sexual harassment to continue their harmful behavior (Cantalupo, 2010; Cunningham et al., 2021; Hulin et al., 1996; Pryor et al., 1993).

Nontransparent practices also foster community perceptions of institutional betrayal by impeding effective sanctioning responses to sexual harassment and facilitating the systemic problem of passing the harasser (Hill, 2018; Serio, 2018). The Harvard case study previously referenced illustrates how the lack of transparency in sanctioning decisions against a faculty member found responsible for sexual harassment enabled the sanctioning conditions to be ignored and unenforced (Harvard University, 2021). Specifically,

the faculty member found responsible for sexual harassment was appointed to multiple committees after being sanctioned—providing him with more leadership authority—even though those appointments explicitly violated the sanctioning terms. The report notes that increased knowledge of the sanctions among those key individuals in a position to monitor them would have increased the likelihood of their enforcement. A lack of knowledge of the sanctions imposed also makes it more difficult for faculty and staff to address repeated offenses of faculty sexual harassment appropriately (Cunningham et al., 2021; Harvard University, 2021; Wiessner, 2017). Keeping sanctions confidential can also perpetuate passing the harasser, as confidentiality and nondisclosure agreements shield faculty found responsible for sexual harassment, enabling them to transition to another position without having to notify their new employer of their prior offense (Brown and Mangan, 2019; Jain et al., 2021; Mervis, 2019).

A related concern is that lack of transparency may lead to “double sanctioning,” whereby a faculty member found responsible for sexual harassment receives a disciplinary sanction from an institutional entity that handles reports of sexual harassment (e.g., the office of equity), but then is still viewed as a perpetrator by others (e.g., faculty and staff leaders) who are unaware of the sanctioning decision, even if the faculty member’s behavior has changed. In this situation, leadership (as well as colleagues) may continue to penalize the faculty member previously found responsible for sexual harassment (and subsequently sanctioned), because they are unaware that any disciplinary action was imposed.

In addition, despite the widespread perception that increased transparency via annual or semiannual reporting of complaints filed and sanctions imposed will improve climate and thereby reduce the incidence of sexual harassment going forward, it is not yet clear that this is in fact the case. Little research exists on how widely such reports are disseminated and discussed within an academic community, or whether the necessarily anonymized and aggregated information provided satisfies a harmed party’s desire for information on the specific punishment meted out to their harasser.

Lack of Consistency in Responses to Sexual Harassment

Responses to reports of faculty sexual harassment can be the responsibility of multiple people across an institution (i.e. department chairs, deans, or faculty disciplinary committees) and often occur without centralized coordination or standards, which can lead to inconsistency in sanctioning decisions or early interventions designed to hold faculty accountable. Consistency in responses to sexual harassment is important for collecting reliable data on how faculty accused of or responsible for sexual harassment are held accountable for their actions. In addition, within a social justice framework, tracking consistency in responses to faculty sexual harassment is important for monitoring equity in sanctioning or early interventions. Inconsistent responses make it difficult to know what policies and practices are being implemented across an institution, as well as how they are being applied. Thus it becomes challenging to evaluate whether the policies or response decisions made are equitable, and whether they are conducive to preventing sexual harassment and building institutional trust (Umphress and Thomas, 2022). Without such evaluation, institutions cannot pinpoint where interventions are needed and how they can improve education, training, or administrative procedures to better address the needs of their community.

One of the first steps in responding to sexual harassment and holding faculty accountable is identifying when harmful behavior is occurring and knowing what one’s reporting responsibilities are. Based on our collective professional experience across diverse positions in higher education, we have observed a lack of consistency in how faculty

and staff identify and report sexual harassment, leading to variation in the responses to such incidents. Many institutions lack effective mandatory training or clear policy language on what behaviors are considered sexual harassment, and as a result, this determination is often left to the discretion of individual faculty and staff (University of Illinois, 2019). Moreover, harmful behaviors are often normalized when pervasive within a department (NASEM, 2018). In addition, gender- or identity-based harassment may be overlooked because a faculty or staff member’s idea of what constitutes sexual harassment leads to the perception that the behavior in question does not yet, or in that one instance, rise to the level of violating an institutional policy (Pérez and Hussey, 2014). Relatedly, this issue may disproportionately impact those with intersecting marginalized identities given the complex ways in which sexual harassment may manifest when combined with other forms of harassment (e.g., racial and sexual harassment) (Buchanan et al., 2009; Calafell, 2014; Cantalupo, 2019; and Jain-Link et al., 2019).

As previously mentioned, decisions on how to hold a faculty member found responsible for sexual harassment accountable are frequently made by individual academic administrators (e.g., deans) or a panel of faculty members, who often have little or no formal training in what the “standard” response or range of disciplinary actions might be for a certain level of misconduct. Many institutions lack documentation on how prior misconduct and other aggravating factors (e.g., frequency of misconduct or violation of nonfraternization policies) should be weighed in the decision-making process. The result is sanctions or early interventions that may differ from department to department within a single institution or across institutions. The University of Minnesota, for example, determined that the lack of visible guidelines on responding to sexual harassment had created community distrust in the institution’s ability to respond consistently and effectively to sexual harassment perpetrated by employees (Buhlmann, 2020). To address this issue, the University of Minnesota developed a set of widely available guidelines and recommendations regarding responsive actions (i.e., disciplinary, rehabilitative, restorative, and monitoring measures) for cases in which an employee (including faculty members) has been found responsible for violating a university policy on sexual misconduct or discrimination following an investigation (University of Minnesota, 2019).

Absent institutional knowledge of how previous cases were handled or consistency in training on how to respond to such cases, we believe academic administrators are likely to treat each case uniquely. In addition, academic administrators may not respond appropriately to less severe cases of faculty sexual harassment if they are unaware of the range of potential actions, and many may only impose termination for the most serious violations of institutional policy (Euben and Lee, 2005b; Salin, 2009). Consistency in sanctioning decisions may also be compromised when new academic administrators approach sanctioning decisions differently from their predecessors or experience conflicts of interest as they consider sanctions based on the needs (e.g., grant funds) of their department or institution (Cantalupo and Kidder, 2019; Stripling and Thomason, 2021; Young and Wiley, 2021).

Lack of Focus on Correcting Behavior through Accountability

In our experience, many institutions have placed insufficient emphasis on how faculty and staff can facilitate early interventions with faculty accused of sexual harassment that prioritize education and accountability over punitive action. Early interventions to hold accused faculty accountable are critical for fostering an organizational climate that is intolerant of sexual harassment (Willness et al., 2007) by preventing the repetition or escalation of such behavior to the level of a policy violation (Cantalupo and Kidder, 2019). Yet the processes for faculty and staff to act on informal reports or

disclosures of such behavior in cases that do not escalate or proceed to the formal investigation stage are often inconsistent because of the lack of clear guidelines on the range of actions that can be taken. Although some institutions enable academic administrators to initiate informal interventions with faculty members upon receiving multiple disclosures of their misconduct absent a formal investigation, guidelines on what accountability or rehabilitative measures can be leveraged in such situations may be unclear. In addition, a lack of guidance or best practices on early interventions can result in “well-meaning” interventions with the potential to cause harm (e.g., requiring the accused faculty member to write a letter to the harmed party).

In addition, it is important for institutions to articulate their expectations of positive behavior in academic and research settings, thereby setting expectations for the entire campus community. In particular, the communications of institutional leaders often influence attitudes toward prevention of sexual harassment (Hart et al., 2018a; Jacobson and Eaton, 2018). Research demonstrates that the messaging and policies of institutional leadership are crucial in building an organizational climate that does not tolerate sexual harassment and in reducing perceptions of institutional betrayal (Bergman et al., 2002; Clarke, 2014; Freyd and Birrell, 2013; Hart et al., 2018b). Thus, it is critical for behavior to be modeled by leadership and for the institutional community to understand the importance of participation in bystander intervention training and other forms of early intervention with faculty exhibiting undesirable behavior.

Areas of Further Research to Improve Responses to Faculty Sexual Harassment by Institutions of Higher Education

The topic of sanctions and early interventions to hold faculty accused of or responsible for sexual harassment accountable, particularly tenured faculty, remains a complex issue with unclear paths to resolution. Although previous studies have outlined possible sanctions for tenured faculty and provided insights on how to develop those sanctions (Cantalupo and Kidder, 2019; Euben and Lee, 2005a; NASEM 2018), there currently exists no readily available document to guide academic administrators in determining appropriate and effective sanctions or early interventions in response to sexual harassment. Further research is therefore needed to determine how to coordinate, implement, and share information on responses to faculty sexual harassment most effectively. This research is crucial for developing evidence-based early intervention and response strategies not only to correct and prevent harmful behavior by faculty members, but also to mitigate community perceptions of institutional betrayal. This section outlines a preliminary research agenda, organized according to the challenges previously discussed, that can yield the information needed to develop such a guidance document.

Coordination

- What are best practices for establishing a central repository or mechanisms for documenting (i.e., keeping an internal record of) actions taken to hold faculty accountable for their sexual harassment behavior within an institution? Additional follow-up questions regarding a central information repository include (1) What office or offices should house such a repository?; (2) Who should have access to the information?; (3) Should faculty members who are the subject of the information have access to the content of the repository, and should they be notified when new information is added?; (4) Should there be a time limit on how long the information is kept (e.g., 10 years, 15 years)?; (5) Should faculty members have the right to respond to the information in the repository, and if the institution has collective bargaining, should this be negotiable?; (6) Should such information be accessible to internal evaluative bodies at the time of consideration for such actions as reappointment, promotion, salary

increase, endowed chairs or other honorifics, or assignment as mentor/advisor/dissertation committee chair, and similarly, should it be available at the time of grant submission?; (7) If allegedly problematic behavior was reported or recorded at any level of the institution but no action was taken, should that information be included in the repository as well?; (8) What, if any, are the legal considerations regarding such a repository?; and (9) Should the information in the repository be available to outside institutions seeking to hire an individual or to professional associations or societies considering the individual for membership, a position of leadership or authority, or receipt of an honor or accolade?

- How should knowledge of any prior or repeated misconduct be used to inform the decision-making processes on holding faculty accountable?

- What are the unique coordination challenges for tracking and responding to sexual harassment by non-tenure-track/adjunct/part-time faculty?

Transparency

- What are the levels of transparency (e.g., individual, department, school, institution), and what does it mean to “go public” (i.e., how is the information shared and who is privy to it)? How can institutions build clarity and more standardization around institutional disclosures to prevent silencing of individuals who have been harmed?

- What are methods for providing transparency without disrespecting/jeopardizing the privacy of individuals involved in a sexual harassment incident? How can the level of transparency that is most appropriate for the harmed party and the accused faculty member, and its potential effect on academic activities, be carefully considered? For example, are there ways to legally inform harmed parties about the actions taken against faculty members involved in their cases?

- When parties sign nondisclosure agreements, what are some ways institutions can respond transparently to the community regarding concerns about the sexual harassment?

- Are there alternatives to nondisclosure agreements or other practices that limit confidentiality, especially in informal response procedures?

- Multiple institutions have started to use annual reports as a vehicle for communicating disciplinary actions taken against faculty found responsible for sexual harassment. Further research is needed, however, to determine whether annual reports are the best method for communicating sexual harassment outcomes, and whether they have the desired effect of demonstrating to the community that the institution does not tolerate sexual harassment. It would also be useful to identify other accessible methods for communicating this information, clarifying institutional practices in this regard, and assessing the long-term impact of annual reporting on improving campus climate.

- Which Action Collaborative members issue annual reports, what is included in them, how are they disseminated (e.g., posted on a website, or posted and then discussed during town halls or department meetings or at deans’ councils)?

Consistency

- What strategies or methods can be used to develop a comprehensive inventory of currently utilized sanctions on faculty found to have violated their institution’s policies against sexual harassment, for all institutions within the Action Collaborative? How can this inventory then be expanded to include members of the Association of American Universities (AAU), the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), liberal arts colleges, and community colleges? Potential research questions to inform the development of this inventory are listed in Appendix B.

- How effective is progressive discipline in correcting behavior, reducing recidivism, and preventing sexual harassment from escalating? Are there models/examples of an escalating

range of disciplinary actions for faculty? If so, have they been evaluated for effectiveness?

- Does progressive discipline affect the likelihood of the harmed parties reporting incidents of sexual harassment? What are best practices for protecting and supporting harmed parties during formal processes for reporting and responding to harmful behavior?

- How should sanctions be handled when the faculty member is part of a bargaining unit and sanctions may be negotiable?

- Do sanctioning responses vary depending on the career stage (e.g., student, postdoc, tenure-track faculty) or employment type (e.g., part-time or non-tenure-track) of the harmed party?

- How can institutions implement consistency in sanctioning responses considering that each situation involves unique factors and circumstances, including the remedies sought by the harmed party?

Correcting Behavior through Accountability

- What trauma-informed early interventions could be employed to help an accused faculty member understand the impact of their actions and ways to change their behavior in an effort to correct sexual harassment behavior as soon as it occurs? How can the effectiveness of these early interventions in correcting such behavior be evaluated?

- What are best practices for documenting and monitoring the behaviors prompting interventions?

- Can bystander intervention, demonstrated to be useful in the student realm, be useful in early interventions involving faculty?

- What are best practices for faculty and staff to support harmed parties throughout early intervention processes and protect them from retaliation?

- What training or guidance on developing and implementing early interventions can institutions provide to academic administrators so that all responsibility does not fall on the chair or dean, and the behavior is dealt with at a lower, less formal level?

- Can faculty-generated statements of expected conduct be of use? Where are such mechanisms being used, and has there been any assessment of their effectiveness?

- If harmful behavior that was initially addressed through informal, early interventions continues or escalates, what are best practices for academic administrators to formally document and report the multiple incidents?

Moving Forward

This paper has provided an overview of the current landscape of response systems for faculty sexual harassment in institutions of higher education and highlighted multiple challenges institutions face in navigating this space. While at the outset, we expected to be able to share evidence-based approaches for addressing the issues we identified, we discovered an absence of such approaches that could readily be applied across institutions. We acknowledge that this paper therefore feels unfinished, and like us, readers may be searching for tangible takeaways for responding more effectively to faculty sexual harassment, as the current system is not working. In that spirit, we have outlined the most important issues we have encountered in our professional work experience, as well as a preliminary research agenda.

In addition to the specific questions listed above, we wish to note a few overarching questions we believe need to be considered in moving forward. We emphasize that these questions are especially relevant in those situations in which the harmful behavior does not meet the criteria for a policy violation, situations that are often more challenging for academic administrators/staff to address. These questions include the following:

- What interim measures can be implemented to protect the harmed party from the potential of further mistreatment or retaliation while investigation and determination of sanctions is underway?

- How can the higher education response system be restructured such that much of the responsibility for handling faculty sexual harassment does not fall solely on academic administrators, who may feel conflicted and often are not experienced or well equipped to respond, document incidents of sexually harassing behavior, or support the harmed parties? In the current system, how can academic administrators be encouraged to more effectively communicate and seek resources (e.g., Title IX coordinators) who are equipped and trained to handle and document sexual harassment cases, especially when the harmful behaviors do not rise to the level of a policy violation?

- We acknowledge that faculty involvement in faculty disciplinary procedures is important for promoting faculty shared governance and for ensuring that sanctioning responses bear in mind the faculty perspective. However, what means can be used to address the academic culture of faculty shared governance that fosters the belief that only faculty can appropriately handle or sanction faculty found responsible for sexual harassment? What methods can be effective in combating the negative impacts of academic star culture on how institutions address faculty found responsible for sexual harassment?

- Are there best practices for engaging funding agencies (e.g., the National Institutes of Health or National Science Foundation) to create a response system consisting of multiple avenues for holding faculty found responsible for sexual harassment accountable?

- Given the current system of faculty and shared governance, how can faculty be persuaded that the current methods for handling faculty sexual harassment are not serving the institution well and often contribute to low retention of graduate students, postdocs, and junior faculty?

- How can appropriately trained professionals (i.e., those who are trauma-informed, as well as knowledgeable about departmental practices and climate) be better integrated into department processes for handling sexually harassing behaviors, particularly those that do not rise to the level of a policy violation, so that academic administrators are better supported (i.e., so the culture is shifted to encourage more connection between academic administrators and these professionals)? Are there best practices for embedding in departments such professionals who are well versed not only in personnel and labor concerns but also in Title IX and Title VII regulations? How can they be positioned so they can have a higher level of authority and more effectively facilitate sharing of best practices for responding to and documenting faculty sexual harassment?

- How are human resources/compliance professionals perceived in higher education communities, and are they perceived differently when they are embedded in a department versus in a separate institutional office? How do offices and/or individual Title IX compliance professionals who are tasked with investigating or addressing sexual harassment complaints minimize experiences of institutional betrayal or distrust among individual community members?

- How do institutions know that the response systems they have put in place work as designed, and how can the effectiveness of such systems be evaluated? When institutions commit to building an organizational climate intolerant of sexual harassment, what means can be used to hold them accountable for that stated commitment?

This paper makes a call for research aimed at systematically gathering evidence on issues of coordination, transparency, and consistency in sanctioning and early interventions for faculty accused of or found responsible for sexual harassment, not only to hold the faculty members accountable but also to support those harmed by this harassment. We believe this call for research is timely given that the preliminary research questions listed here align closely with AAU’s recently released principles on preventing sexual harassment in academia (AAU, 2021). We are hopeful that such research efforts will generate the evidence-based practices and approaches that are so urgently needed to resolve the issues highlighted throughout this paper.

Appendix A: Early Interventions to Correct Behavior Through Accountability

Many institutions have begun exploring the use of interventions focused on equipping faculty and academic leaders with the skills to intervene both proactively and retroactively when confronted with behaviors that fail to align with their institutional values (Connor et al., 2021; Hayes et al., 2020; Hickson et al., 2007; Paulin et al., 2018; Pichert et al., 2013). Some institutions offer individual and group coaching opportunities to enable their faculty and leaders to learn and practice having difficult conversations. In these sessions, faculty have an opportunity to practice with peers and receive real-time feedback. These trainings offer an opportunity for members of the community to learn how to engage where they previously may have been reluctant to step in.

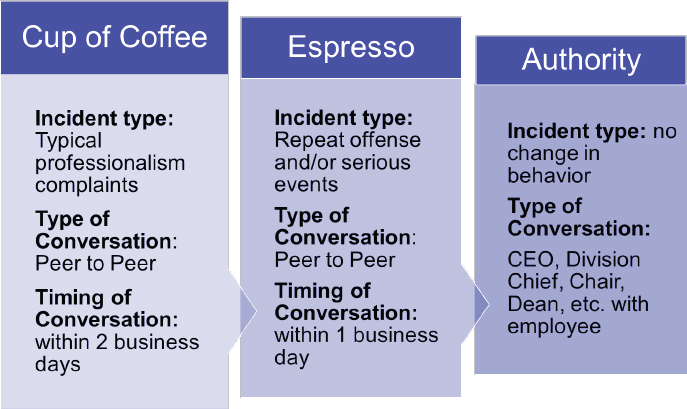

Several models exist whereby an incident triggers a process.8 The University of California, Davis, has instituted a mechanism called “documented discussions” (UC Davis, 2019). Another model, used in the Duke Health System and based on a model developed at Vanderbilt University (Hickson et al., 2007), enlists peers from across the Health System to engage in conversation when a report of poor behavior is received (McNeill, 2020). Known as the “cup of coffee” program, this program trains messengers to invite colleagues for a brief chat to discuss an incident of poor behavior (see Figure 1). These conversations are intended to be informal, and superiors are not informed. For all individuals with repeat complaints, however, the conversation is escalated to an “espresso” for a second peer-to-peer conversation. If the behavior does not change, a leader with higher authority is enlisted to have a more serious conversation with the individual.

__________________

8 Pappas and colleagues have also discussed multiple informal resolution options in the context of Title IX, which may be useful for designing early interventions (Pappas et al., 2021, pp. 754–759).

Evaluation of the cup of coffee program at the Duke Health System and Vanderbilt University has shown that frank dialogue with a peer can be effective in changing behavior. Of the 85 individuals who have had a cup of coffee conversation within the Duke Health System, only 3 have had to meet for a second time for an espresso conversation (Paulin et al., 2018). In 70 percent of cases at Vanderbilt University, those who have had a cup of coffee conversation have had no repeat complaints (Paulin et al., 2018). Given its effectiveness in the Duke Health System, the program may be transferable to nonmedical academic settings.

Finally, many institutions are also exploring bystander intervention trainings specifically for academic leaders and faculty members (Bean, 2021; Connor et al., 2021; Florida International University, 2021; Meltzer and Heron, 2021; The Pennsylvania State University, 2015), in which participants learn useful skills for engaging and diffusing situations. More research is needed, however, to understand the optimal frequency of these trainings and their overall effectiveness.

Appendix B: Potential Research Questions to Support Development of a Comprehensive Inventory of Sanctions

Theoretically Possible Sanctions

- Does the institution have a specific catalog of sanctions that can be imposed on those found to have violated institutional sexual harassment policies?

- If yes, are there recommended sanctions associated with particular offenses or a particular range of offenses?

- Is the severity or frequency of sexually harassing behavior a factor in sanctioning? How does the institution keep track of harassing occurrences, some of which may be “low level,” such that the frequency of such behavior is accurately known? Also, is there a specific length of time institutions should track these occurrences for faculty members?

- Is the catalog of possible sanctions included in publicly available sexual harassment guidance documents?

- Is the catalog otherwise broadly disseminated to the community? Is it discussed in public forums (e.g., department and school meetings), and if so, how frequently and in what context?

Consistency in Sanctions Actually Imposed

- Does the institution keep a historical, central record of sanctions actually imposed and the related policy violations? Is that record readily available to all members of the community? If not, is it available to those responsible for determining sanctions?

- How many years does this record cover? Have the sanctioning advice and the actual sanctioning changed over time? Have sanctions become more or less “severe”? When and why?

- If there is no current central record, might one be constructed by centralizing decentralized records? Is there any institutional plan to do so?

- Is there any mechanism for ensuring university-wide consistency of sanctions in real time or on a post hoc, annual basis?

- Is legal liability a concern if sanctions are not consistent across schools/colleges in the same university for the same offense?

Transparency of Sanctions Imposed

- Is the sanction in a particular case made known to the college/university community in real time—e.g., in the academic year in which the sanctioning occurs? If so, how? As an individual case? In the aggregate? In an annual report? What is the means of communication, and does any campus conversation ensue?

Responsibility for Sanctioning

- What individual (title/position) or what office (academic affairs, employment equity, human resources, general counsel, etc.) is responsible for determining the sanction? Does the sanctioning title or office differ depending on the status of the accused faculty member—e.g.,

part-time, full-time, adjunct/temporary, non-tenure-track, tenure-track, or tenured faculty? Does the sanctioning responsibility differ depending on the status of the harmed party—e.g., undergraduate student, graduate student, postdoc, faculty, staff?

- If the sanction is determined by an individual, is that individual required to consult with or seek approval of anyone else? Are there any checks on this person’s authority?

- If the accused faculty member is tenured, is a faculty committee involved in the sanctioning process, or is shared governance somehow otherwise involved?

Training

- Is training or guidance provided to chairs, deans, provosts, and other academic officers in appropriate sanctioning of faculty members? What individual or office provides such training? Should such academic officers be responsible for sanctioning members of the faculty? If not, where should the responsibility lie?

Assessment

- Does the institution assess the impact of the severity of a sanction or the use of any particular sanction on (1) discouraging repeat offenses, (2) discouraging new offenses, (3) preventing sexual harassment or gender discrimination, and (4) improving organizational climate? If so, via what mechanism and how often? If not, how best might such impact be measured?

Collective Bargaining

- If there is collective bargaining at the institution, is sexual harassment (and the issue of discipline and/or sanctions) covered in the collective bargaining agreement?

References

1. AAU (Association of American Universities). 2021. AAU principles on preventing sexual harassment in academia. https://www.aau.edu/aau-principles-preventing-sexual-harassmentacademia

2. AAUP (American Association of University Professors). 2016. The history, uses, and abuses of Title IX. https://www.aaup.org/file/TitleIXreport.pdf

3. Aguilar, S. J., and C. Baek. 2020. Sexual harassment in academe is underreported, especially by students in the life and physical sciences. PLOS ONE 15(3):e0230312. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230312

4. Bean, C. 2021. Public summit of the Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education: Translating sexual harassment research into effective training practices for academic leaders. [Video]. https://vimeo.com/showcase/9224717/video/670870806

5. Bergman, M. E., R. D. Langhout, P. A. Palmieri, L. M. Cortina, and L. F. Fitzgerald. 2002. The (un)reasonableness of reporting: Antecedents and consequences of reporting sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology 87(2):230. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.230

6. Brown, S. 2015, October 22. Why colleges have a hard time handling professors who harass. Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/why-colleges-have-a-hard-time-handling-professors-who-harass

7. Brown, S. and K. Mangan. 2019, June 27. “Pass the harasser” is higher ed’s worst-kept secret. How can colleges stop doing it? Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/pass-the-harasser-is-higher-eds-worst-kept-secret-how-can-colleges-stop-doing-it

8. Buchanan, N. T., M. E. Bergman, T. A. Bruce, K. C. Woods, and L. L. Lichty. 2009. Unique and joint effects of sexual and racial harassment on college students’ well-being. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 31(3):267–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973530903058532

9. Buhlmann, P. 2020. Public Summit of the Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education: EOAA recommendations for responsive action at the University of Minnesota. [Video]. https://vimeo.com/showcase/7711364/video/471563430

10. Calafell, B. M. 2014. “Did it happen because of your race or sex?”: University sexual harassment policies and the move against intersectionality. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 35(3):75–95. https://doi.org/10.5250/fronjwomestud.35.3.0075

11. Camera, L. (2021). Education department begins sweeping rewrite of Title IX sexual misconduct rules. US News & World Report. https://www.usnews.com/news/education-news/articles/2021-06-07/education-department-begins-sweeping-rewrite-of-title-ix-sexual-misconduct-rules

12. Cantalupo, N. C. 2010. How should colleges and universities respond to peer sexual violence on campus? What the current legal environment tells us. Georgetown Law Faculty Publications and Other Works 431.

13. Cantalupo, N. C. 2019. And even more of us are brave: Intersectionality & sexual harassment of women students of color. Harvard Journal of Law and Gender 42:1. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3168909

14. Cantalupo, N. C., and W. Kidder. 2018. A systematic look at a serial problem: Sexual harassment of students by university faculty. Utah Law Review 3:671–786. https://dc.law.utah.edu/ulr/vol2018/iss3/4

15. Cantalupo, N. C., and W. Kidder. 2019. Systematic prevention of a serial problem: Sexual harassment and bridging core concepts of Bakke in the #MeToo era. UC Davis Law Review 52:2349–2405.

16. Cantor, D., Fisher, B., Chibnall, S. H., Townsend, R., Lee, H., Thomas, G., Bruce, C., and Westat, Inc. (2015). Report on the AAU campus climate survey on sexual assault and sexual misconduct. https://www.aau.edu/sites/default/files/AAUFiles/Key-Issues/Campus-Safety/AAU-Campus-Climate-Survey-FINAL-10-20-17.pdf

17. Cipriano, A. E., Holland, K. J., Bedera, N., Eagan, S. R., and Diede, A. S. 2021. Severe and pervasive? Consequences of sexual harassment for graduate students and their Title IX report outcomes. Feminist Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1177/15570851211062579

18. Clarke, H. M. 2014. Predicting the decision to report sexual harassment: Organizational influences and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Organizational Psychology 14(2).

19. Connor, R., J. Cusano, S. McMahon, K. Padovano, K. Stubaus. Stubaus, K., S. McMahon, K. Padovano, J. Cusano, and R. Connor. 2021. Public summit of the Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education: Bystander intervention in harassment situations: Measuring behavior and adapting student prevention models for faculty and staff. [Video]. https://vimeo.com/showcase/9224717/video/670847044

20. Cunningham, P., M. E. Drumwright, and K. W. Foster. 2021. Networks of complicity: Social networks and sex harassment. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion 40(4):392–409. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-04-2019-0117

21. Curtis, A. E. 2017. Ignorance, intent and ideology: Retaliation in Title IX. Harvard Journal of Law and Gender 40:333, 362.

22. DOE (U.S. Department of Education). 2020. Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Sex in Education Programs or Activities Receiving Federal Financial Assistance. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-05-19/pdf/2020-10512.pdf

23. Euben, D. R., and B. A. Lee. 2005a. Faculty misconduct and discipline. Presentation to National Conference on Law and Higher Education, February 20–22, 2005. Rutgers University. New Brunswick, New Jersey. https://www.aaup.org/issues/appointments-promotions-discipline/faculty-misconduct-and-discipline-2005

24. Euben, D. R., and B. A. Lee. 2005b. Faculty discipline: Legal and policy issues in dealing with faculty misconduct. Journal of College and University Law 32:241.

25. Flaherty, C. 2017, July 18. Worse than it seems. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/07/18/study-finds-large-share-cases-involving-faculty-harassment-graduate-students-are

26. Flaherty, C. 2019, March 12. The case for disciplining faculty harassers. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/

news/2019/03/12/new-paper-says-slapping-faculty-harassers-wrists-compromises-comprehensive

27. Florida International University. 2021. Bystander leadership. https://advance.fiu.edu/programs/bystander-leadership/index.html

28. Freyd, J. J. 2018. What sexual assault victims speak out, their institutions often betray them. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/when-sexual-assault-victims-speak-out-their-institutions-often-betray-them-87050

29. Freyd, J. J., and P. J. Birrell. 2013. Blind to betrayal: Why we fool ourselves, We aren’t being fooled. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

30. Hart, C. G., A. D. Crossley, and S. J. Correll. 2018a. Leader messaging and attitudes toward sexual violence. Socius. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023118808617

31. Hart, C. G., A. D. Crossley, and S. J. Correll. 2018b, December 14. Study: When leaders take sexual harassment seriously, so do employees. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/12/study-when-leaders-take-sexual-harassment-seriously-so-do-employees

32. Harton, M., and Benya, F. (Eds.). 2022a. Innovative practice: University of Wisconsin System. Stop “passing the harasser” policy. Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.17226/26564

33. Harton, M., and Benya, F. (Eds.). 2022b. Innovative practice: University of California, Davis, stop “passing the harasser” policy. Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.17226/26565

34. Harvard University. 2021. Report of the external review committee to review sexual harassment at Harvard University. https://provost.harvard.edu/files/provost/files/report_of_committee_to_president_bacow_january_2021.pdf

35. Hayes, T., L. Kaylor, and K. Oltman. 2020. Coffee and controversy: How applied psychology can revitalize sexual harassment and racial discrimination training. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 13(2):117–136. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2019.84

36. Hickson, G. B., J. W. Pichert, L. E. Webb, and S. G. Gabbe. 2007. A complementary approach to promoting professionalism: Identifying, measuring, and addressing unprofessional behaviors. Academic Medicine 82(11):1040–1048. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31815761ee

37. Hill, A. 2018, July 19. Reporting sexual harassment: Toward accountability and action. The Gender Policy Report. University of Minnesota. https://genderpolicyreport.umn.edu/reporting-sexual-harassment-towards-accountability-and-action

38. Holland, K. J., Hutchison, E. Q., Ahrens, C. E., & Torres, M. G.. (2021). Reporting is not supporting: Why mandatory supporting, not mandatory reporting, must guide university sexual misconduct policies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(52), e2116515118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116515118

39. Hulin, C. L., Fitzgerald, L. F., and Drasgow, F. (1996). Organizational influences on sexual harassment. In Sexual harassment in the workplace: Perspectives, frontiers, and response strategies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Pp. 127–150. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483327280.n7

40. Jacobson, R. K., and A. A. Eaton. 2018. How organizational policies influence bystander likelihood of reporting moderate and severe sexual harassment at work. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 30(1):37–62.

41. Jain, S., A. Salles, and V. Arora. 2021, June 25. Let’s stop passing the buck on sexual harassment in academic medicine. The Cancer Letter. https://cancerletter.com/guest-editorial/20210625_4

42. Jain-Link, P., T. Bourgeois, and J. T. Kennedy. 2019, April 23. Ending harassment at work requires an intersectional approach. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/04/ending-harassment-at-work-requires-an-intersectional-approach

43. Johnson, S.K., J. F. Kirk, and K. Keplinger. 2016, October 4. Why we fail to report sexual harassment. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/10/why-we-fail-to-report-sexual-harassment